In Conversation with R.H. Thomson

R.H. Thomson’s career on stage, screen and television has spanned 50 years. Although well-known for Anne with An E, Atom Egoyan’s Chloe, and CBC programming, his work in support of veterans is also garnering critical acclaim.

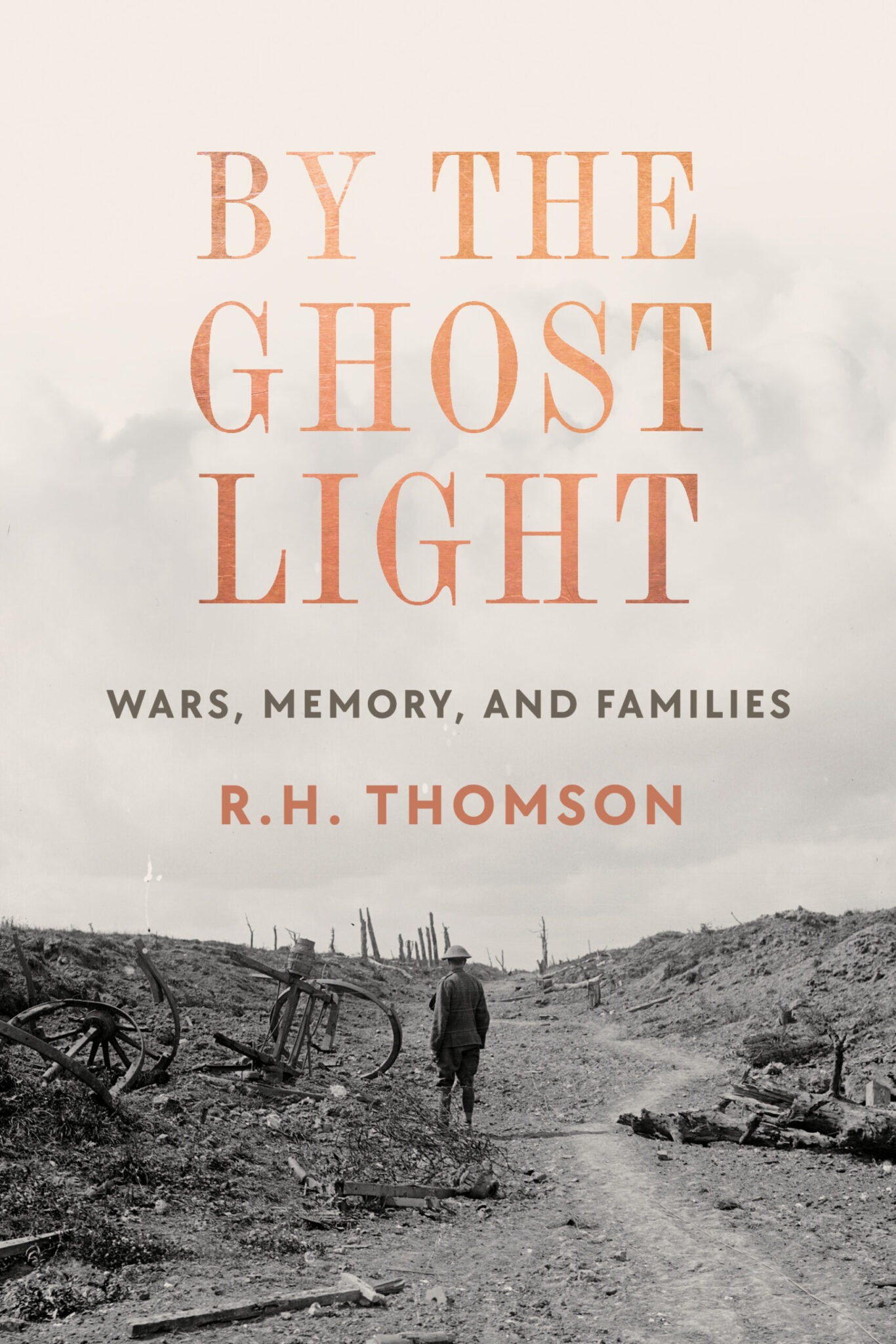

For the First World War Centenary, Thomson created The World Remembers, an ambitious international project to name each of the millions killed in the war. As a follow up, Thomson has now penned, By The Ghost Light, an extraordinary look at his family’s history, providing a powerful examination of how we understand war and its aftermath.

Truly original in scope, By the Ghost Light, will challenge the way we approach our history. We sat down with the award-winning actor to discuss The World Remembers, family, and his new book.

The Collection: What is The World Remembers?

RH Thomson: The World Remembers addresses an absence in Remembrance Day ceremonies…the names. Whether it’s the First World War, the Second, the Korean War…the people are the important thing. So, on Remembrance Day, we should name the thousands that were killed. This began as a Canadian idea with just 68,000 Canadians. We named them on buildings, on the National War Memorial, on Trafalgar Square in Canada House. We then persuaded groups across the country to put the names on legislatures and on churches. Seeing someone’s grandfather’s name appear, and being told when it would appear, meant a lot to people. When that happened, I believed we had to do everyone from the First World War…and that’s both sides: French, German, British, American, Slovenian, Italian.

TC: Do you include the names of “enemy” nations?

RT: After we did the first one on Toronto City Hall, a woman come up to me and said, “Thank you. That is the first time I ever felt included on November 11th. I grew up in Stratford, but my family came from Germany. We all go quiet on Remembrance Day. Nobody remembers us.” Well, is Remembrance Day for who we were in 1914 or is it for who we are now? And do you still say they’re the enemy? Germany is our biggest NATO partner. If you exclude them, you’re still playing the division game. After 100 years, the division game should be over. The last thing we need now is more division.

TC: Why did you pursue this initiative?

RT: I did a play (The Lost Boys). Afterwards, people would come up and start telling me their stories. I realized that I’d tapped into something. People want their stories told. And often when you get people talking, their stories are pretty powerful. They should all be part of the history.

TC: How many countries are participating?

RT: We’ve just added our 23rd country, Romania. We’re slowly putting together the database. It’s hard because a lot of research hasn’t been done, but we’re now up to 4.2 million names.

TC: There’s an anecdote in the book about you getting into the Russian archives. Did anything change since then?

RT: The moment Russia went into Crimea, I couldn’t go near them. Russia should be part of the project, they lost more than anybody else, but they’re busy bombing their way through Ukraine.

TC: Why is your book titled By the Ghost Light?

RH: A ghost light is what we put in theatres when everyone goes home for the night. It stands on stage, illuminating the space, to ensure no one falls off. Theatres are places where we tell stories, and when you stand by the ghost light, you see things, you hear stories. So, it’s a bit like if you went back to your grandmother or grandfather to tell you stories. You’re asking them to stand by that light and pull the memories out so you can see them.

TC: Throughout the book, you share several of your family’s wartime letters. What does the retelling of personal war stories teach us that history books cannot?

RH: That there are no simple points of view. We tell the stories afterwards and it tends to clean things up and simplify them. There’s the enemy, there are the people that won. It’s more complicated. If you listen to the veterans, it’s very complicated. We, as civilians, tend to want it simple, but to make a very simple story out of war belies history, is not true to history, and can often lead you to very destructive places.

TC: The letters also feature women, whether mothers at home or nurses in the field. How do their perspectives differ from the men in the field?

RH: Dynamics work differently, men carry different baggage and expectations. You can’t generalize, there’s no hard and fast rules, but ask yourself if The English Patient had been written by a woman, what would it be like? These letters also remind us that women were on the receiving end of a lot of it. Not only what turned up on the operating table, but what turned up at home when men came back from war. Women were on the receiving end… as were the children. War doesn’t stop with the bullets. War continues. It’s multi-generational. These scars ricochet down through kids and grandkids. So how do we deal with that? How do we speak about that? That’s also partly why I spend the time with the women. They’ll say things that a man wouldn’t say. Would a man talk about a soldier who cried or a soldier who killed himself?

TC: The German artist, Kathe Kollwitz, is a recurring figure in the book. What would you want the reader to know about her?

RH: We all know the propaganda stories, but we don’t hear the story from a woman who says “I’m dealing with starving children, I’m dealing with poor people, people who I don’t think should be meeting their deaths. How do I remember that?’” Her artistic expression as seen through the two statues, The Grieving Parents, is a statement I couldn’t ignore.

TC: The letters reveal a variety of viewpoints. Joe with his bravado, Isabel with her patriotism, Margaret with her matter-of-fact nature. You offer a different take, but you also have the luxury of not living it.

RH: Yes, I’m telling from the safety of not having to live it. If I was writing in 1916, would I have written that…but then that brings you to Kathe Kollwitz again. She wrote in 1916, knowing how unpopular her view was, so I don’t know. I don’t have a right to extrapolate their feelings, but I do try to say, when they say to me as ghosts, that you have a right to tell our story.

TC: What do you think your family would say about the book?

RH: We’ll find out. There are many branches to the family, some are more progressive than others. I know there will be some resentment, but it’s the truth, and I’ve honoured all those great uncles in a way. Their stories should be told.

TC: What does Remembrance Day mean to you?

RH: Remembrance Day is important. I do wish we could do more. With The World Remembers, we do the projectors with the Canadian War Museum every November. Then year-round, we’ve designed an interactive screen and kiosk where you can choose a country and language and look at pictures. It has the 4.2 million names, and every year, we add more. I’d like one of them in the Peace Tower. The tower was built to promote peace.

With this kiosk, any visitor to Ottawa could go to the Canadian Peace Tower and look up a Pakistani name or Romanian name. That’s peace. The American Museum just agreed to install a kiosk, and we’re trying to raise money to get one at the Vimy Memorial in France. Most of the visitors there are French and German students. I’m trying to get one in their information centre so the students can look for their own great grandfathers’ names. And I want them to know it was a Canadian who said everybody should be remembered, because that’s who we are now.

For more information on The World Remembers, visit theworldremembers.org

For more information on By The Ghost Light, visit penguinrandomhouse.ca