By Kaitlin Wainright, Heritage Toronto (Originally published in COLLECTIONS by Harvey Kalles Real Estate, Winter 2015)

Stepping out onto Yonge Street south of Lawrence Avenue, the manicured landscape of Alexander Muir Memorial Gardens is difficult to miss. Described by an international jury as “a transition from the everyday life of the streets to the city’s bucolic ravine system,” the park, designed in 1951 by Edwin Kaye, also serves as the western border for one of Canada’s first garden suburbs and one of Toronto’s most well-appointed addresses – Lawrence Park.

As noted by Construction magazine in 1911, the development of suburbs was one of the defining social movements at the turn of the last century. Following an economic depression in the 1890s, cities were again booming. Toronto, in particular, saw an increase in its population by 80 percent during the first decade of the 20th century. Many viewed this demographic growth in the old city as a serious threat to physical health, social mores, and family values.

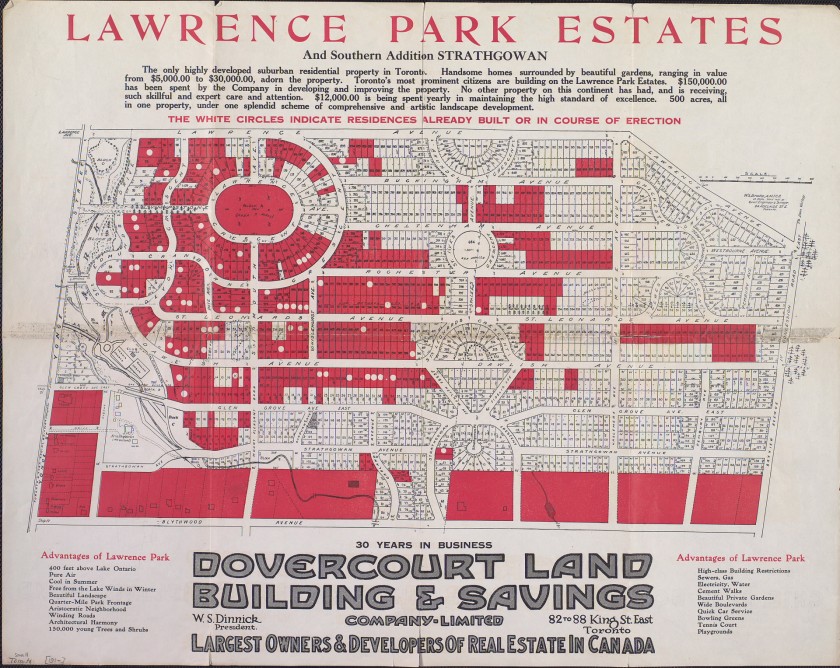

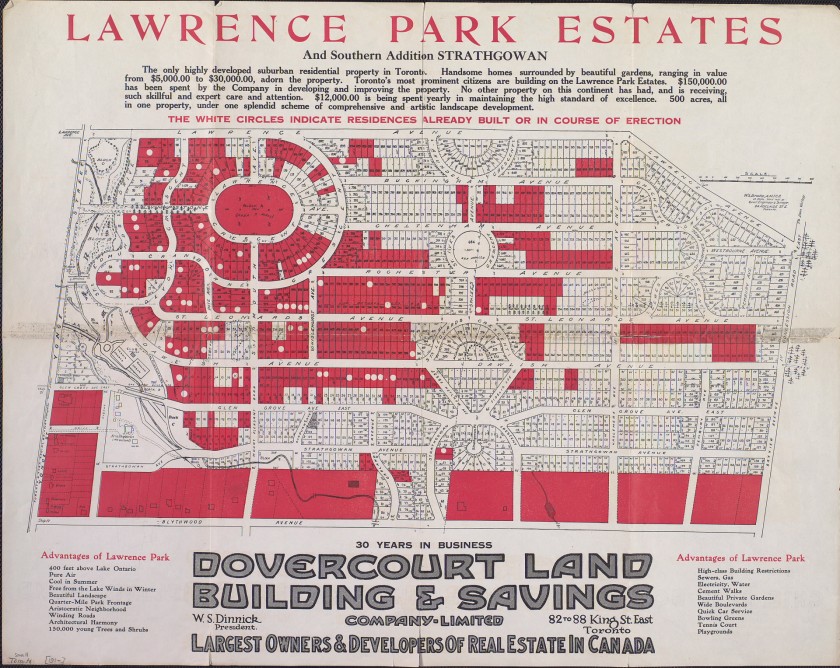

In response to concerns about urban densification, Wilfrid S. Dinnick, president of the quickly expanding Dovercourt Land, Building and Savings Company, convinced his Board of Directors to invest in suburban development. The venture came on the heels of the Garden City movement; British social reformer Ebenezer Howard’s internationally influential planning ideals that urged low-density development surrounded by a permanent belt of agricultural land.

The company purchased land in 1907 on Lots 4 and 5 in North Toronto and York Township, which was prime real estate, “on high ground of rolling hills and open spaces, interspersed with ravines and mixed woodlands, and traversed by a tributary of the Don River.” It also didn’t hurt that this was one of only a handful of previously undivided properties within easy distance of Toronto.

Dinnick’s vision for Lawrence Park was inspired by Letchworth (1903) and Hampstead (1907), two early garden suburbs laid out in England. As a model for controlling urban sprawl, the garden suburb relied on low density, pristine gardens with open spaces, and minimal local industry. In pursuit of a modern picture of physical health and social well-being, Dinnick wanted his well-heeled residents to retire each day from the sounds and smells of the city to the pure air and the idyllic purity of family life found in the countryside. A promotional pamphlet described Lawrence Park as “a formal and artistic grouping of ideal homes.”

Early plans for the Lawrence Park subdivision, designed by engineer W.S. Brooke, show winding crescents, circles and cul-de-sacs that intermingle with straight streets, and generous lots with space enough for a house, garage, and a substantial garden. Under Dinnick’s direction, there was as much emphasis on a property’s garden as there was on its house. In 1913, he instituted a Toronto-wide backyard garden contest. With the onset of the First World War, this became a vegetable garden contest, to the great benefit of King and Country.

The extensive landscaping of Lawrence Park’s properties featured generous formal entrance courts, croquet lawns, and terraces. Dinnick kept a nursery on the east side of the subdivision, where homeowners and builders could acquire various plant specimens at cost, while decorative bridges, rockeries, and fountains were provided by Dovercourt. The company also promoted the construction of a lawn bowling clubhouse with tennis courts, anticipating that the promise of refined recreation would bring gentrified clients.

In 1909, believing that building activity would spur sales, Dinnick had Dovercourt commission architects Vaux Chadwick and Samuel Beckett to design seven homes. These were not model homes, but houses for immediate sale and occupancy. Chadwick and Beckett were the official architects of Lawrence Park for the next five years. If a property owner wanted to hire other architects, plans needed to be approved by Dovercourt.

Dinnick and his family lived in one of the first houses, at 77 St. Edmund’s Drive. He spared no expense in the home’s construction or landscaping, so that it could be used in early publicity. The exterior featured stunning Tudor Revival elements, but the pièce de résistance was the dining room ceiling and frieze, graced with the brush of Gustav Hahn, who created impressive murals in such public buildings as the Ontario Legislature and Old City Hall in Toronto. Hahn was not the only artist who captured (or was captured by) Dinnick’s vision. A founding member of the Group of Seven, J.E.H. Macdonald, created early promotional material for the neighbourhood.

Greatly valuing the relationship with both his family and his business, Dinnick had a house constructed for his mother and sister. Located just 200 metres away from his own home, at 35 St. Edmund’s Drive, the Dovercourt Company called this property Buena Vista in its advertising. A real estate pamphlet points out, among other highlights, that a stone wall was erected around the entire property “with imposing gates giving entrance to the driveway and garage.” Save for a portion at the rear of the property, the stone wall and its gates have since been demolished.

Between 1909 and 1915, the suburb grew, though not as much as originally hoped. With the First World War, the real estate market collapsed and construction ceased. After the war, Lawrence Park never quite rebounded, with its financial challenges compounded by a worsening economy and a revised tax law, which taxed unimproved lands.

In 1919, the Dovercourt Land, Building and Savings Company was taken over by Sterling Trusts, which authorized the sale of previously unsold subdivided lots. “Every lot will be sold without reserve no matter what price it brings.” By 1930, 221 single family dwellings had been built in Lawrence Park, mostly to the west of St. Ives Avenue. (Among them, 43 Rochester Avenue was the home of Group of Seven artist A.J. Casson; look for his blue Heritage Toronto Legacy plaque.) To the east were fields that had gone to waste, overgrown with hawthorn bushes. The Great Depression and Second World War meant that the remainder of Lawrence Park took until the 1950s to be fully built out. At that time, some double lots were divided and new housing emerged on what had once been side gardens.

Despite extensive renovations and rebuilding in the community, Lawrence Park has retained its leafy appearance and low density, and the area has only become more prestigious with the passage of time.

Kaitlin Wainwright is the Plaques and Markers Program Coordinator at Heritage Toronto. Live in a century house? Celebrate your home’s history with a Heritage Toronto plaque or century house number. Contact Kaitlin at 416-338-0679 or [email protected] for more information .