The 25th Annual ScotiaBank CONTACT Photography Festival

By Louise Nunn

We communicate in images. More than ever before, our lives, news, and current issues are filtered through the lens of images. In 2015 the world was rocked by the heartbreaking picture of a little boy, Alan Kurdi, washed up on a beach. His photograph woke many up to the devastation of the Syrian refugee crisis. As the world looks back on 2020, images of ICU beds, plastic barriers, and protests will sum up powerfully a year of pandemic and deep unrest.

Camera lenses have the power to burn into our memory the social issues and current events of our time – truths that may be uncomfortable but are nevertheless immortalized through images. Photography has become one of the art forms that moves as fast as the digital world and is accessible to everyone with a phone, but even still presents deeply insightful perspectives. By clicking the shutter at just the right second, a photographer has the power to capture the electricity of a single moment and change perspectives.

“We communicate with images more than ever right now,” says Darcy Killeen, Executive Director for CONTACT Photography festival. “Just think of the riots on Capitol Hill. Documentation of that was incredible. People are communicating what’s happening, and it’s communicated to the public almost live. It really is amazing. And our artists are doing the same thing. They’re dealing with very important issues and putting them at the forefront with the use of photography.”

Take Esmaa Mohamoud’s The Brotherhood FUBU (For Us, By Us), which will be one of the many public installations headlining CONTACT Photography’s 25th anniversary festival in May: in a large-scale outdoor installation that presents two Black men as the subject in two separate pieces, Mohamoud, an African-Canadian artist based in Toronto, confronts her audience with questions on race and gender. Part one, a giant 145-foot photographic mural, pictures two Black men staring straight out at the viewer. Their posture and sparse accessories – simple silver bracelets and a du-rag or wave cap draped over one shoulder – arrests the passersby with the fragile and vulnerable side of these men. Mohamoud complicates the mainstream depiction of Black men with this tender and intimate alternative – which is made all the more poignant and surprising by its placement at the Toronto waterfront, such an open public area, alongside a life size cast-bronze sculpture of these same men.

Strollers along the Toronto waterfront will see Mohamoud’s mural or her sculpture and instantly be brought into a public conversation that has been ongoing in Toronto and the world. Engaging the city has always been a central purpose of the festival’s Public Installations program, started in 2003. “Our big focus is on trying to present very significant, large-scale, outdoor public art installations…this year, we’re planning 20 public installations” says Darcy Killeen. The hope for The Brotherhood is that non-art audiences will pass the Black men represented in the photo mural and think back to Toronto’s own track record of policing, or take a second look at the vulnerability depicted in the sculpture and reconsider a prejudice they had once held. “With [an installation] that size, you know, you can’t walk by and not experience it or see it; you will be engaged with it no matter what.”

But in CONTACT, the size of a public work won’t be the only thing that will turn the heads of artists and pedestrians alike. Equally important is the location. CONTACT is the festival where local and international, renowned and up and coming lens-based artists will take over billboards, subway stations, and the city’s top art institutions. Thirza Schaap’s Plastic Ocean will be displayed at Toronto’s Dupont subway station. Her eerily beautiful pastel seascapes – created out of used up consumer products and photographed against a backdrop of sand and sea – will draw the eyes of masked subway goers as they wait idly for their train. The Dutch artist based in Cape Town will connect Toronto’s platform waiters to a global conversation about climate change. One of much international talent that CONTACT draws for its month-long festival, Thirza will position her series right along the subway platform – a territory where ads for new consumer products usually dominate the walls. Each photograph is made entirely out of the trash that Thirza collected from her walks near the ocean. Here in the concrete underground of a subway platform, the newest products are touted to potential consumers. Thirza Schaap and the team at CONTACT ask viewers: what better place is there than this to begin a conversation about the end of these products’ life cycle?

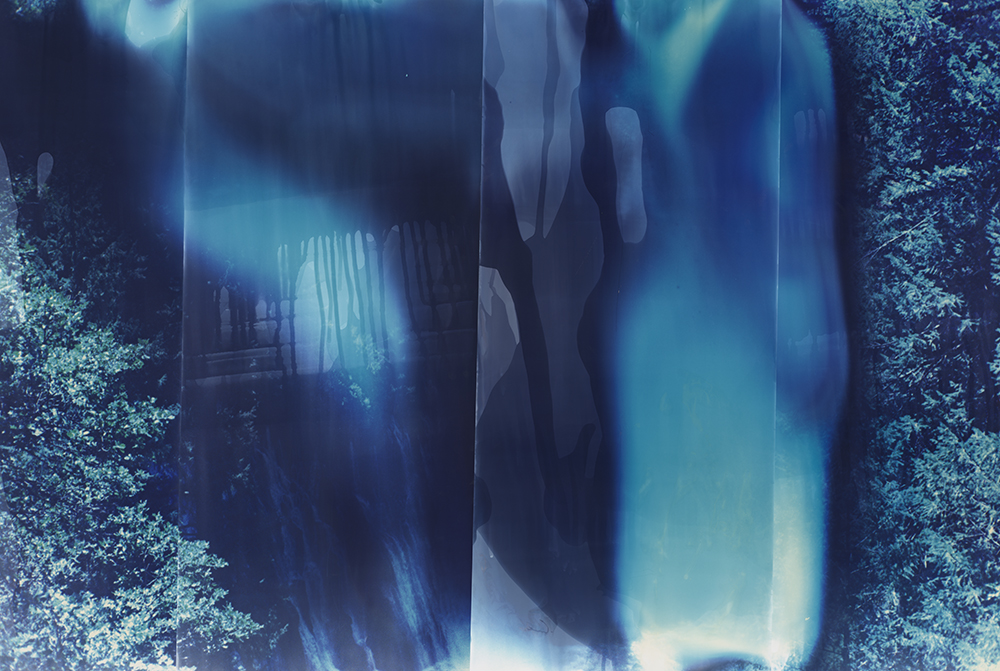

According to Darcy Killeen, CONTACT hopes that the site-specific exhibits around the city will really “startle viewers into a new consideration of their environment,” and like Thirza’s subway-based Plastic Ocean, the group exhibition Force Field at Fort York should do just that. Besides news images of protests calling for racial justice and coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a lot of coverage in Canadian media and art around Indigenous activism. The recent land disputes over the natural gas pipeline have sparked a countrywide conversation on the fraught history of Canada-Indigenous relations. Force Field, curated by Indigenous-settler artist Logan MacDonald, will take over the whole of the Fort York historic site with a collection of the work of Indigenous, queer and disabled creators from the community. It will be a way for the curator, the artists and the public to reflect thoughtfully on what version of history historic sites preserve and how marginalized and BIPOC artists might join the dialogue. Through its 2021 Year of Public Art Initiative, ArtworxTO, the city is taking a second look at public spaces of all kinds and funding public art projects in the midst of a pandemic that has hit the creative world hard. BIPOC artists like Esmaa Mohamoud, Greg Staats, Skawennati, Frida Orupabo and Logan MacDonald go further in the conversation of public space: their art asks who exactly is comfortable in these spaces, and wonders how marginalized groups can reclaim these spaces or lands. CONTACT’s artists answer through their photography.

“We are here to celebrate the art form of photography” Darcy explains, “that is our core mission and vision. And we do that by supporting Canadian artists and building an international platform for them”. As one of the world’s top photography festivals, CONTACT draws the highest photography talent from around the world and partners with top art institutions in Toronto, like the AGO and Ryerson University. But it is the voices of all artists, both established and emerging, that CONTACT is concerned with. Darcy explains, “the majority of festivals in the world only deal with those top two tiers, and there’s no real place for the very young or emerging. But in CONTACT, it’s amazing that many, many photographers have their first exhibition as part of CONTACT as a vehicle for them to show their photography. So if you looked at CONTACT’s artists index, you would have the biggest name in photography there, and you would also have a first time photographer, or a guy showing his travel pictures, or somebody showing you baby pictures – it could be anything. That’s really a distinguishing point of CONTACT.”

As the world waits for the distribution of the vaccine to turn public gatherings and crowded art fests back to normal, Toronto needs a festival that recognizes the evolving ways we make contact with one another and express ourselves. CONTACT and its artists will capture the issues that connect us through the camera…even if the locations might look a little different this year. For the 25th, the festival will be celebrated in COVID-safe outdoor, indoor, and virtual spaces.

For more on the ScoriaBank CONTACT Photography Festival, visit scotiabankcontactphoto.com