Art Gallery of Ontario presents the work of Denyse Thomasos

By Jordan Z. Adler

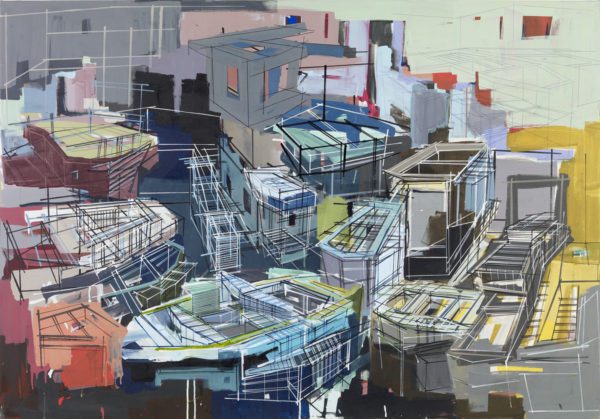

In the abstract paintings of the late Trinidadian-Canadian artist Denyse Thomasos, it is hard to know what to look at first. Many of her artworks are on giant canvases, filled with striking patterns and a palette’s worth of colour.

Several of Thomasos’ paintings – such as Arc (2009), made on a 6-by-3 metre canvas, and Metropolis (2007) – reveal a cityscape where futuristic-looking machines and architecture seem to encroach on a vibrant urban space. Thomasos’ most startling paintings evoke a sense of chaos and claustrophobia.

As curator Sally Frater explains, the time is right for a comprehensive look at Thomasos’ art and life. Many of the themes within this portfolio of work – prisons, surveillance, sprawl, the future of cities – resonate within the contemporary political landscape across Canada and the United States.

“We’re in a perfect moment, in looking back at Thomasos’ work and the multitudes it contained, to see how forward-thinking, how prescient her work was,” Frater says. “Her work is compelling on so many levels.”

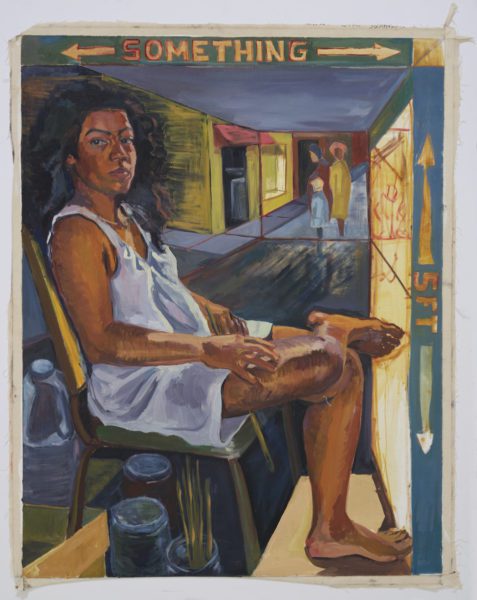

Denyse Thomasos: just beyond opens on the fifth floor of the Art Gallery of Ontario on October 5 and runs until February 20. More than 70 of Thomasos’ paintings and artworks will be on display. Several of them explore the Black experience and fuse the past, present, and potential futures.

The exhibition’s title comes from a quote by artist Julian Kreimer. As he described Thomasos’ wall work, “they capture the scale of the world but they were of a scale just beyond one’s ability to take in all the world, its joys and suffering.”

It is that feeling of being engulfed in the world of her paintings that inspired the name of this retrospective, Frater says.

The structures and spaces in several of these paintings are those that confine the body. These environments include slave ships, prisons, and cramped urban neighbourhoods. However, there are no people visible in the artwork.

“We know that specific groups of people had these types of architecture [used] against them. [But] you don’t actually see bodies undergoing that suffering,” explains Frater. “In some ways, she’s disrupting these cycles of violence.”

“She manages to disrupt our association with, say, Blackness and the abject through not having bodies in there. The other side to that is, as the viewer, you are implicated in those spaces. Thomasos’ experience as an immigrant offered her a perspective that could encompass these feelings of exile, discrimination, and alienation,” Frater says.

Born in Trinidad in 1964, Thomasos immigrated to Toronto with her family in 1970, fleeing political turmoil. Living in Toronto, her interest in world events and social activism began to take shape. “This exploration of movement and migration…that underpin her work, I feel like they first took root here in Canada, in Ontario,” Frater says.

As a Black woman, she also had numerous encounters with racism while living in Toronto. Curious to understand Black culture and history better, Thomasos became an avid reader and researcher. Her social consciousness was apparent early. As a student at the University of Toronto in the mid-to-late 1980s, she protested against South African apartheid. Alongside her rigor as an artist, she was committed to conducting research and raising awareness. Thomasos wanted to know more about the transatlantic slave trade and other migrant experiences…common themes that would inform her art.

One can find this interplay with the past, for instance, in Burial at Gorée (1993). This haunting mural-sized abstract painting refers to Gorée Island, a place off the coast of Senegal that was also a prominent center of the slave trade.

“She doesn’t allow for [escapism] in her work,” Frater says. “She’s able to convey the sense of the suffocating confinement of those spaces.”

After graduating from the University of Toronto, and Yale University’s School of Art, Thomasos spent much of her adult life in the United States. Although working from a studio in Manhattan’s East Village and teaching art at Rutgers University, she remained a fixture in the Canadian art scene. Just beyond will also feature documentary footage of the artist working in her studio in Manhattan’s East Village. The footage was filmed by her widow, artist and filmmaker Samein Priester, and captures the detail and precision in Thomasos’ creative process.

At just 47 years, Thomasos life would end suddenly in 2012 from a rare allergic reaction during a diagnostic procedure. Although just beyond is considered the first major retrospective of Thomasos’ work, she was recently featured in the 2022 Whitney Biennial in New York. At this exhibit, a haunting triptych of paintings – evoking prisons, slave ships, and burial sites, sometimes within the same canvas – became among the Biennial’s biggest draws.

The upcoming retrospective’s title, just beyond, also evokes a sense of possibility beyond the punishing spaces depicted in her paintings. One can see these hints of optimism in some of Thomasos’ later works. Her 2011 wall painting, Kingdom Come, is awash in greener hues, revealing her interest in eco-friendly architecture and the possibility for harmony and utopia.

However, as Frater interprets, not everyone can access green space, such as those living in the margins. Even within a more utopian world, divisions and inequality remain. “Even in the future, there’s this reckoning with race and class and carceral systems, as opposed to the way in which we often envision the future, which is as this utopic space,” Frater says of Kingdom Come.

“We believe that she rendered them in the hopes that we would grapple with these historical and present horrors, to move to something beyond them.”

For more information, visit ago.ca