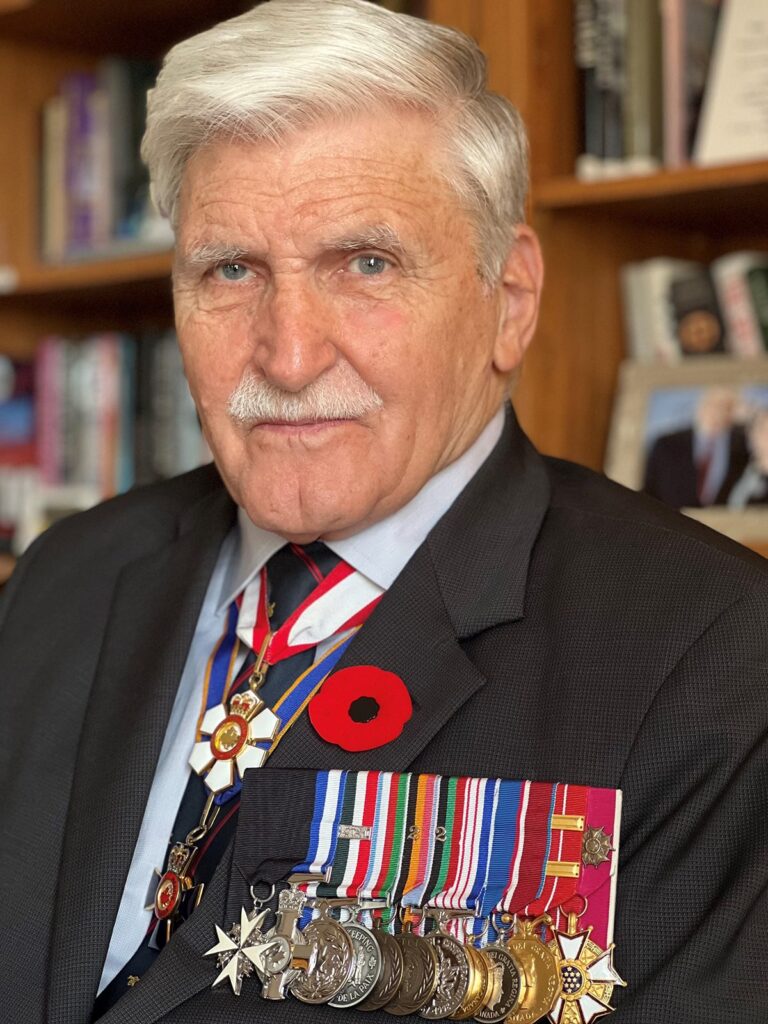

IN CONVERSATION WITH GENERAL ROMÉO DALLAIRE

General Roméo Dallaire is a global human rights advocate, author, political advisor and former Senator. Famous for his leadership during the 1994 Rwandan genocide, he continues to bring international attention to issues ranging from the use of children in armed conflict to the impacts of PTSD on veterans and their families.

In his new book, The Peace, General Dallaire calls for a revised approach to global peace. He critiques the failures of international interventions, while proposing a future where humanity prioritizes collective well-being and environmental stewardship.

The Collection sat down with the renowned humanitarian to discuss his vision for a world where “the peace” is not just an ideal but a reality.

The Collection: In The Peace, you found inspiration in Dante’s Divine Comedy, taking the reader through three tiers: Hell, Purgatory, and Peace. Why did you choose this structure?

GENERAL ROMÉO Dallaire: Our research focused on the fact that we are in a revolutionary period. A period where we must shift gears in a number of arenas, from our handling of the planet to social changes of extraordinary dimensions. So, when was the last time [we witnessed] fundamental revolutionary thinking? During the Italian Renaissance. We went back and found the genesis for much of the Italian Renaissance came from Dante, his work, and that poem. And it struck me that he was right. As he was trying to achieve his heaven and peace with God, we have never achieved our peace. We’ve fiddled with truces, conflicts we thought solved, but within five or ten years, they regenerated.

TC: You write that we confuse ‘peace’ with ‘the absence of war.’

RD: Let me give an example. In 1945, World War II ends, the world is now at peace. But within weeks, we’re opening up a new front with the Soviet Union. With time, we’ve got an iron curtain, we’ve got a wall. We never really had peace. This was a failure in the creation of the nation states, created out of war, where nations thought that by creating states they could establish processes for peace. We’ve been living through a series of truces. But peace means lasting peace. Peace doesn’t mean stop shooting. That has no legs. There are so many frictions not addressed in peace agreements and conflict resolution that they blow up again.

TC: The Peace explores how qualities like hate, deceit, ignorance, fear, and revenge keep nations stuck in your lowest tier.

RD: And the worst one is greed. Greed is driving the whole exercise and is going to undermine our ability to stop the abuse of resources. The drive for more power, the search for assets…We’ve got to be able to overcome. As an incentive, there is reason for lasting peace, which is not just absolute security. There is a role for humanity beyond this planet. We’re fiddling with trying to get there versus [tapping] the comprehensive capability of all humanity in communion with the planet to thrive and go beyond itself.

TC: At home, we’ve seen a rise in hate crimes.

RD: We’re dominated by self-interest. We are simply managing what we can by reacting, and there’s little desire for prevention. That comes from the lack of political will, courage, commitment to take risks, and to go beyond what the institutions have established as parameters.

One institution that has established very low-level parameters is the media. The media has essentially moved down to the level of how to keep Grade 9 students informed. It’s gone perverse, destroying all the decency and civility in the processes of political decision making. So, we are reacting to an instrument that has brought us lower when it is supposed to guide us higher.

TC: How imperative is empathy in the pursuit of peace?

RD: Without empathy, without a sense of communion between human beings, there will always be the frictions of differences, even though we are all equal. Not one human is more human than the other. But we let the frictions of nuances fester because we haven’t established that fundamental state of treating the other as an equal.

We should be searching for instruments to make it happen beyond the normal structures of UN conventions. Human beings are fundamentally empathetic because we want communion with our equals. We are not an isolationist instrument.

TC: What is human security?

RD: Human security is a concept where all the dimensions of a human being’s life are in a state that would permit the being to thrive…to be able to meet its aspirations without looking behind its back. It’s everything from social justice, to economics, to political well-being, to physical security, to the right to dominate decision making. It covers the full spectrum of what human beings need to be able to advance without expecting something pejorative to curtail that.

TC: Do open immigration policies jeopardize human security at home by adding pressure on a nation’s limited resources?

RD: It is not pejorative, where nations have a capacity to offer people an opportunity. These nations should be constructing their social programs to take advantage of the potential of these human beings for the future of the nation, versus trying to count the numbers that are coming in. This is human potential that is being offered up to us. We should be building processes in which we can make them move forward, for them and their future generations, and to find the respect for the nuances of what they come with, from their ethnicity to their religion.

TC: If achieving peace requires a unifying ideology, what is that ideology going to be?

RD: That all humans are equal. It is based on respect…nothing less. Respect gives you the ability to adapt, to be able to nurture, to evolve, to change, because there’s no threat in respect. On the contrary…there is a desire to learn, a desire to move forward.

TC: Do you still have hope that the 21st century will kickstart a new period of enlightenment, what you call the “Millennium of Humanity?”

RD: The two elements I believe will be the catalysts of the future are, one, women are equal…we’ve changed the philosophies of the male dominated institutions based on a male philosophy of leadership; and the second, the young are going to master the technology to leap ahead. So I’II say, two centuries…it may be one, it may be three. That’s a very small period of time…we’ve been slaughtering each other for over 10,000 years.

Gisozi, Kigali, Rwanda: Rwandan Genocide memorial names wall – an estimated 500,000 to 1 million Tutsis (70% of the total population) and moderate Hutus were murdered over a 100-day period from April 7 to July 15, 1994. Most of the killings were committed by two Hutu militias, the Interahamwe, and the Impuzamugambi.

Gisozi, Kigali, Rwanda: Rwandan Genocide memorial names wall – an estimated 500,000 to 1 million Tutsis (70% of the total population) and moderate Hutus were murdered over a 100-day period from April 7 to July 15, 1994. Most of the killings were committed by two Hutu militias, the Interahamwe, and the Impuzamugambi.

TC: This year marks the the 30th anniversary of Rwanda. Your own trauma has been well documented. Thirty years on, how are you doing?

RH: Five years ago, I was suicidal, after 20 odd years of therapy. In a camouflaged way, I was working myself to death and doctors had given me two years. There was no solace to be found until I discovered this woman. I discovered something called love that I had never had, and that broke the code. It is love that will permit people to overcome the components that could be negative and that will help you thrive, continuing to advance in a positive way. Love is the component that brought me into a contract for another 25 years of thriving versus hoping that the end would be soon.

For more information on The Peace,

visit penguinrandomhouse.ca