By Jacqueline Nunes

From afar, many of Brian Jungen’s sculptures appear to be recognizable as Indigenous artistic and cultural objects: animal masks, feathered headdresses, woven blankets, totem poles and teepees. But a closer look reveals a shockingly untraditional use of materials. The blankets are woven from sports jerseys; the totem poles are assembled out of golf bags; and the masks and headdresses are made entirely of deconstructed Nike Air Jordans. “He’s managed to find the feather in the sole of the Nike sneaker and the fur or tufting in the shoelace,” says Kitty Scott, the curator of a new exhibition of Jungen’s work for the Art Gallery of Ontario, which opened on June 20. “It’s quite extraordinary to see how he has taken apart the sneaker and used every part, treating the sneaker as he would if he were using an animal.”

An artist of mixed Indigenous and European heritage (his mother was from the Dane-zaa Nation and his father was Swiss), Brian Jungen is world-renowned for his sculptures and installations made from repurposed consumer goods. Many of the masks and headdresses are part of a series called Prototypes for a New Understanding (1998-2005) that transformed sneakers into sculptures resembling Northwest Coast masks and Plains Indian headdresses. In the press release for the AGO exhibition, Jungen, who grew up in Fort St. John, British Columbia, says, “My work is largely about transforming things, but these sneakers also speak about where I come from. Nike Air Jordans are popular among Indigenous youth.”

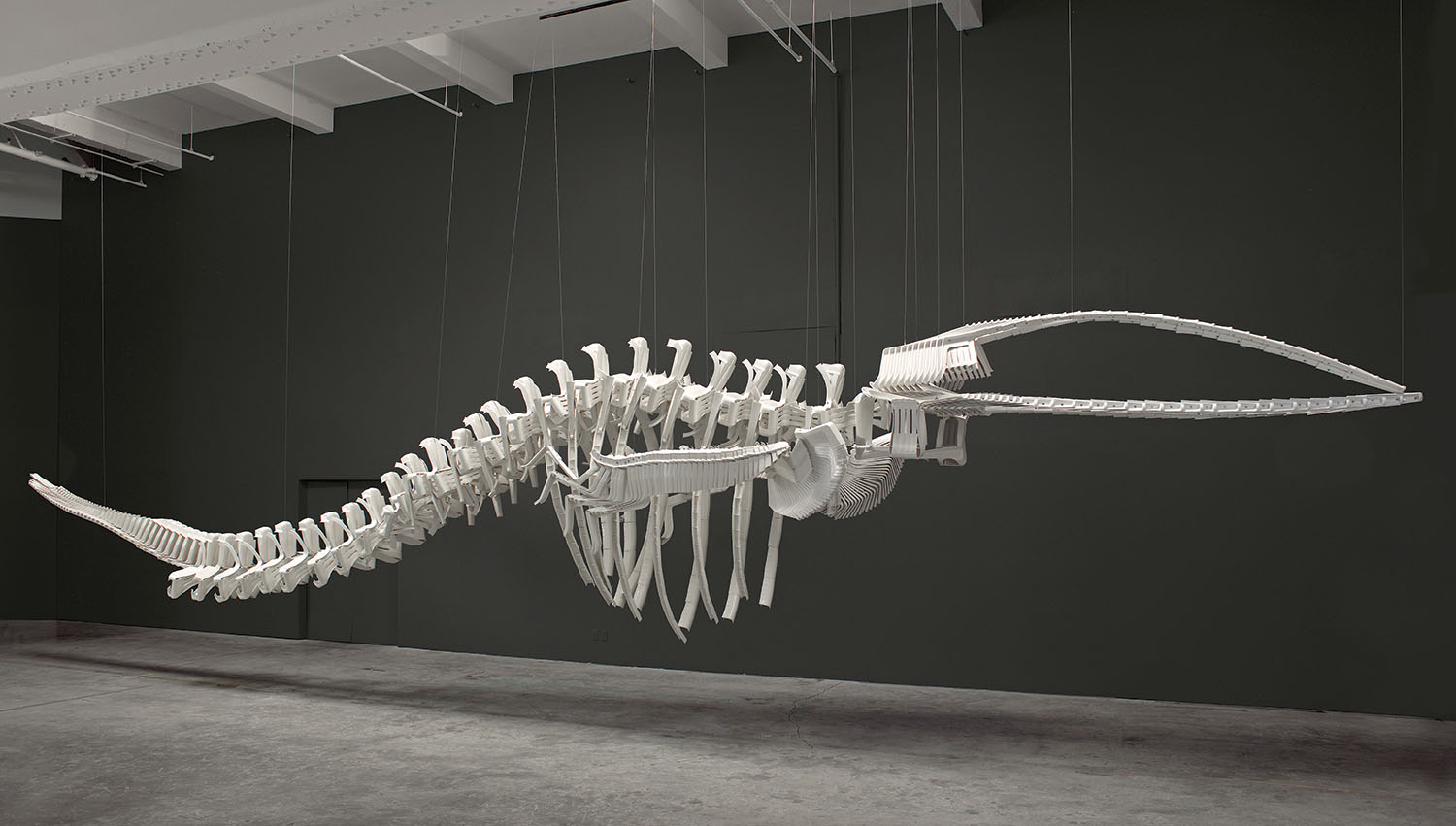

Another highlight of the exhibition is Cetology (2002), a 40-foot long sculpture of a whale skeleton constructed out of plastic patio chairs, which is on loan from the Vancouver Art Gallery and will be suspended from the gallery ceiling. And one of his most formidable pieces, Furniture Sculpture (2006), is a 27-foot-tall teepee that Jungen made by skinning 11 leather couches and using their wood frames to make poles. The artist got the idea when his band council was distributing funds from a land claims settlement. He noticed that some members were using the money to buy leather couches, according to a story he told when he became the first living artist to have a solo exhibition at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. “I thought it was this crazy icon of wealth. But there’s a lot of hide in them,” he told the Smithsonian magazine at the time. The teepee will be on display in the AGO’s Walker Court for three weeks of the exhibition run, only the second time it has been exhibited, due to its size.

The exhibition is titled Friendship Centre, referring to community organizations where urban Indigenous people can access health, employment, cultural and youth services. “For Brian, the Friendship Centre is an open, welcoming place that bridges across cultures,” Scott says, “and he wants to overlay that onto the AGO and think about it as a new kind of Friendship Centre.” Another recurring image in Jurgen’s work is the gymnasium, which is a gathering place in many Indigenous communities. Scott explains, “The gym is a place where you can have sports events. It’s a place where you can have pow-wows. It’s a place where you can have community meetings and band meetings.” She adds, “Brian is thinking about the AGO as one-part Friendship Centre and one-part gymnasium, and he’s going to transform one of the spaces in the AGO into this kind of communal space. It’s a brand new work.”

In total, the exhibition will present more than 80 artworks, including new headdresses, masks and other reimagined pieces, such as Jungen’s jerry cans. Scott points out, “You often see them in rural communities. People have them in the back of their pick-up trucks and use them for water or gas.” Using a hand-drill, the artist creates patterns in jerry cans, “sort of the reverse of traditional beading techniques. The patterns are ornate and really beautiful but they also render the jerry can useless. Instead of gas, it is filled with light,” Scott says. And the exhibition will also mark the debut of a new director’s cut of Modest Livelihood, a film co-starring and co-directed by Jungen and the artist Duane Linklater. Shown simultaneously on five screens, this film installation will run through more than seven hours of footage, detailing a series of hunting trips made by the artists.

“But what I think is really going to give deep insight into his ways of thinking and making are his archives,” says Scott, referring to the 2,000-plus photographs exhibited alongside the Nike shoeboxes Jungen has been collecting since 1998. These containers hold his precious items, materials for future works, scraps of sneakers and other objects. The never-seen-before photographic archives, which will be displayed on three large screens, include Jungen’s research for many of his iconic pieces, such as photos of every totem pole in Vancouver taken when the artist was creating his golf-bag totem poles, and of different sofa models when he was creating his sofa-skin teepee. “It will be a complete revelation,” Scott says. “He also has a deep connection to land and to nature, so you’ll get a sense of somebody who’s spending a lot of time outdoors and his experiences in those moments come back into the work in different ways. People who already know Brian Jungen will have a whole new understanding.”

The exhibition is also the first time that the AGO will host a solo-presentation by an Indigenous Canadian artist in the Sam & Ayala Zacks Pavilion. “Those are amongst the most prestigious galleries,” Scott says. “We haven’t had very many living artists in that space.” The exhibition reflects an important shift happening at the AGO to focus more on Indigenous artists, which has included two major Indigenous exhibitions over the last year. The first revolved around the artistic and family ties of two of Inuit art’s biggest names, Kenojuak Ashevak and Tim Pitsiulak; and the second featured Rebecca Belmore, a multimedia artist and member of the Lac Seul First Nation (Anishinaabe), highlighting “the artist’s lifelong commitment to natural materials, to the body, and to the act of listening,” according to Wanda Nanibush, the AGO’s Curator of Indigenous Art.

The AGO also undertook a massive renovation and renaming of the J.S. McLean Centre for Indigenous and Canadian Art to “showcase contemporary Indigenous art in conversation with Canadian art, and to highlight critical discussions about identity, the environment, history and sovereignty,” says Nanibush. In recognition that the AGO is located on Mississauga Anishinaabe territory, all the texts in the McLean Centre are trilingual — in Anishinaabemowin, English and French. The Inuit collection features texts in Inuktitut, along with English and French.

“Brian is one of the most interesting artists working today, and Toronto has only hosted small exhibitions of a few of his artworks,” Scott says. “This will be the first time people living in this city have been able to see a wide array of his work, from very early works to a deep dive into his sculptural and installation works.” She is particularly excited to share her favourite works by the artist: large drum-like forms created by covering modernist furniture in animal hides using traditional techniques. “His work on many levels gives shape and form to the Indigenous experience today. I think it’s something that many people want to know about, want to learn about, want to experience.”

The exhibition Brian Jungen: Friendship Centre is on view at the Art Gallery of Ontario from June 20 to August 25.

For more information, visit www.ago.ca.