AGO presents new exhibit on the life of Leonard Cohen

By Jordan Z. Adler

Leonard Cohen’s deep baritone and evocative lyrics created an allure of mystery around the poet and singer/songwriter who died in November 2016. Although a fixture of Canada’s cultural scene since the 1960s – and an internationally-renowned star who, even in his late seventies, could sell out concerts across the world – Cohen also embraced privacy.

This elusiveness offers room for various surprises during an upcoming Art Gallery of Ontario exhibition on Cohen’s life, art, and music. Entitled Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows, the show will feature more than 200 creative works and objects that once belonged to Cohen, and are now part of his family trust.

The exhibition’s purpose is not solely to chart Cohen’s wide-ranging career as a poet/singer/songwriter. It will also explore how these objects and ephemera from Cohen’s archive are just as valuable to understanding him as are the artist’s enduring poetry and songbook. Many of these materials from the late musician’s personal archive have never been shown publicly.

Everybody Knows opened at the AGO for the gallery’s members on December 7, and for general admission on December 13. To Julian Cox, the curator of this exhibition and the AGO’s deputy director, among the most exciting finds on display are Cohen’s journals and notebooks.

“He always carried a pocketbook with him, wherever he went,” Cox tells The Collection. “He would use those notebooks to jot down lyrics and ideas for songs and for poems and novels.”

The notebooks with some of the draft verses for “Hallelujah” will likely be, for many fans, a highlight of the exhibition. It took Cohen years to finalize the lyrics for that song.

These personal journals span nearly 50 years, from the early 1960s, when Cohen was a nascent poet and writer trying to make his mark in Montreal, to the years encompassing a world tour between 2008 and 2010.

What the notebooks also reveal, Cox explains, is the musician’s playfulness and wit, as well as his painstaking attention to detail. Cohen even returned to these writings years later, marking and revising, while also mining them for new ideas to use in songs and other artworks.

Other objects of fascination – for their simplicity and sense of play – include Cohen’s drawings. These range from doodles on napkins to pictures he would draw when he had young children. Cohen’s son, singer/songwriter Adam, has revealed that his father used to wake early to write and draw, and would share his pictures with the children when they woke.

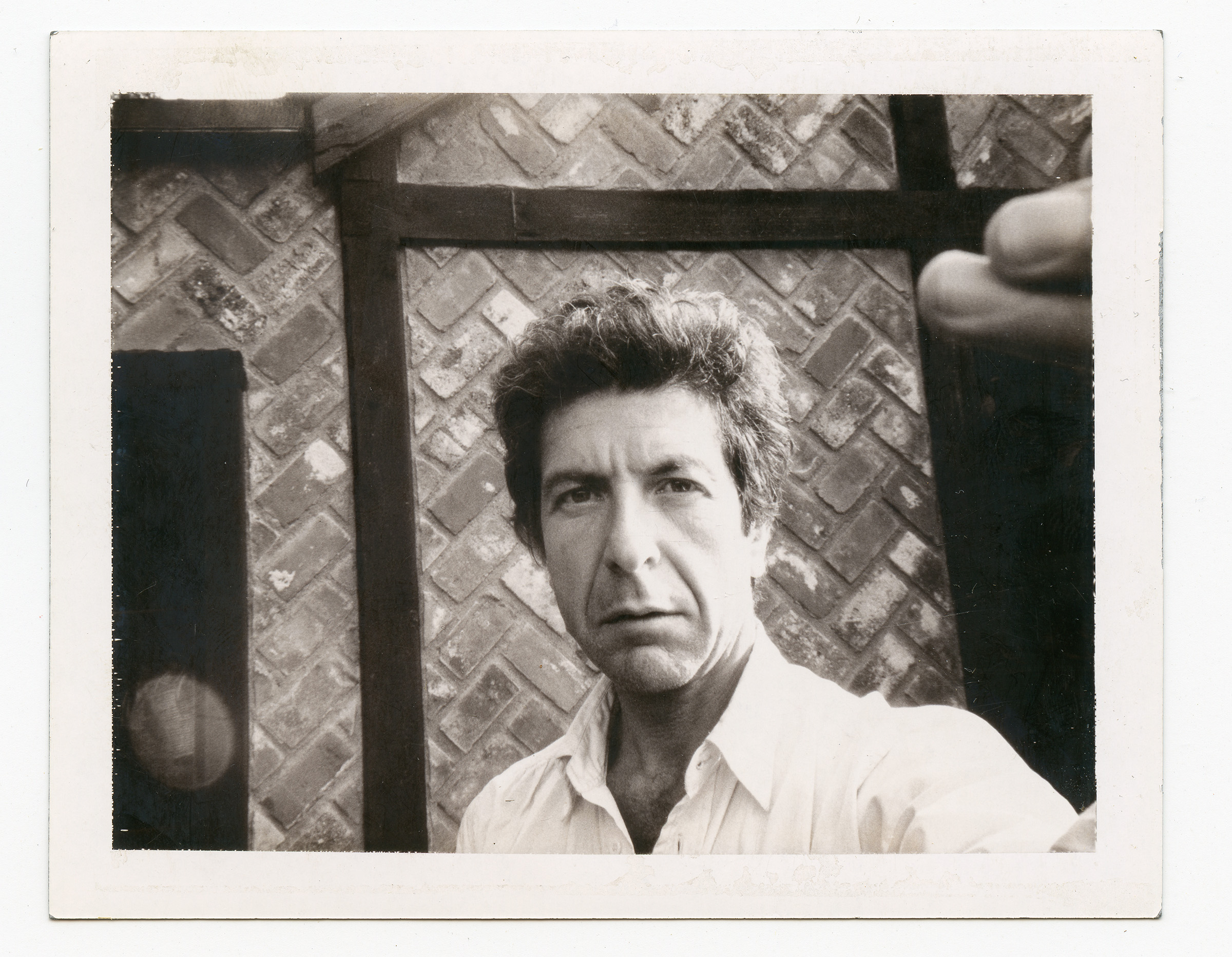

Other revealing expressions of Cohen’s life come in the many photographs accompanying this exhibition. As Cox says, Cohen owned many cameras from the 1960s onward, as well as different types of Polaroid film, and used them for both the mundane and professional.

“He understood the power of the photograph to help shape his public persona,” Cox says, adding that he made these photographs “in a very disciplined way, almost as a daily form of self-expression and journaling.”

Among the most fascinating Polaroid images are from the late 1960s, when Cohen was transitioning from being a writer and poet to a recording artist.

These photographs are documents of his time in Nashville, where he was preparing to make his second album, Songs from a Room, and finding his foot in the American music scene. Some of those images of Cohen from Nashville were taken by the late Toronto photographer Arnaud Maggs.

Everybody Knows will also feature fan mail, personal letters (from, among others, Joni Mitchell and k.d. lang), books from Cohen’s personal library, musical instruments, and even Cohen’s trilby hat.

Nevertheless, the show is structured around crucial settings within Cohen’s life. An early section will focus on Cohen’s roots within Montreal and the city’s Jewish community.

“That’s fundamental to who he is,” Cox says. “This is someone who explored many different religions and spiritual systems throughout his life. But in a sense, it always came back to Judaism and his love of the Jewish stories and the spoken word, as it’s communicated by the cantor [in a synagogue].”

Other locations emphasized here include the Greek island of Hydra. There, after purchasing a three-storey home in 1960, Cohen found both beauty and privacy. He fell in love with Marianne Ihlen, the inspiration for the beloved song, “So Long, Marianne,” in Hydra, and also wrote much of his early poetry and literature there.

Some of the drafts of those early prose and poetry were even sold to the University of Toronto around the time of Cohen’s 30th birthday. The artist wanted to curate his own life story and create a record for posterity.

“From very early on, the idea of an archive was really important to him,” Cox says. “He’s on the record as saying he considers the archive to be his sort of masterpiece… not just the many collections of poems and the novels and the albums, but the entire body of work.”

The point of the exhibition’s title, Everybody Knows, is meant to be ironic: there is much known about Cohen, but still much left for his fans and admirers to excavate within the memorabilia.

Of course, the exhibition shares its name with Cohen’s hit 1988 single, an ominous track where one can still see modern-day relevance. As Cox indicates, one of the haunting lyrics intones that “the Plague is coming,” which resonates with a song written in pre-COVID times. (It has been interpreted as a reference to the AIDS crisis, which raged at the time of the song’s release.)

“I don’t describe Cohen as a prophet or a seer in any way,” Cox says. “But there is no doubt about it, that he had an uncanny way of cutting to the core of the human experience in a lot of his songwriting, and the poetry especially.”

For more information, visit ago.ca